The abacus was man’s first recorded adding machine. Developed in China, the abacus is an ancient computing device constructed of sliding beads on small wooden rods, strung on a wooden frame. You could call the abacus the first calculator.

How is an abacus related to computing?

The main idea behind computing hasn’t changed since the invention of the abacus: if a certain set of rules can solve problems, then a machine can be built to follow those rules and calculate answers. An abacus follows a simple set of rules to quickly solve math problems.

Who invented the first recorded mechanical calculator?

In 1642, a French mathematician named Blaise Pascal invented the first mechanical calculation machine. He called it the Pascaline. The Pascaline was made out of clock gears and levers, and could solve basic mathematical problems like addition and subtraction. You may have heard of a modern-day, computer programming language named in his honor: Pascal.

Blaise Pascal and the Pascaline

How was the Pascaline improved?

The first individual to improve upon Pascal’s design was a German mathematician named Gottfried Wilhelm von Liebniz. In 1694, he created a machine similar to Pascal’s called the "stepped reckoner." Leibniz’s machine could perform all four basic arithmetic functions: addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. However, his machine was often inaccurate.

In 1820, Charles Xavier Thomas de Colmar invented the "arithometer." Colmar’s machine could also perform each mathematical function, but with total accuracy. Together, Pascal, Gottfried, and Colmar defined the age of mechanical computation, and paved the way for later computers.

What is a punched card?

In the 1800s, computer technology got a boost from an unlikely place: Joseph Jacquard’s fabric weaving loom. Jacquard’s loom relied on cards—with holes punched in them—which allowed fabric patterns to be "programmed."

Why is the punched card important?

The punched card was adapted for use in early computers and provided computer programmers with a new way to put information into their machines. Until only two decades ago, the punched card was the most popular method for entering data into computers.

Who was the first person to successfully use punched cards?

The first person to successfully use punched cards—specifically for census taking—was Herman Hollerith. By the 19th century, the number of people in the United States was so large, it took seven years to count them all.

Seeking to shorten that time, the Census Bureau held a contest to find the fastest adding machine. Hollerith won the contest with his punched card device, and his invention helped to complete the 1890 census in just two and one-half years. Hollerith’s successful use of punched cards in gathering and storing information made him the father of information processing. Hollerith later went on to found the Tabulating Machine Company, which later became the Computer Tabulating Recording Company. Hollerith retired in 1921, but his company went on to become a part of the International Business Machines Corporation. We know it today as IBM.

Who is the father of computing?

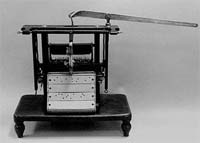

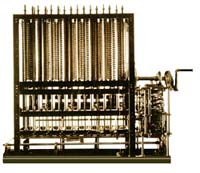

In 1821, Charles Babbage invented the first, modern computer design: a steam-powered adding machine called "the difference engine." Babbage understood that long math problems were just repetitive operations. Therefore, Babbage made a machine to automatically solve math problems.

Charles Babbage and Analytical Engine

Babbage also invented the "analytical engine." The analytical engine was a mechanical adding machine that took information from punched cards to solve and print complex mathematical operations.

Why are the difference and analytical engines Important?

Babbage's difference engine and the analytical engine are regarded as the first "thinking machines." These machines were made for people who weren’t math experts. The difference and analytical engines were easy to operate and produced solutions at the turn of a hand crank. Babbage's inventions earned him the title, "father of computers." Unfortunately, Babbage’s two designs were too far ahead of their time, and neither design could be built during his lifetime. However, in 1991 the London Science Museum built the difference engine based on Babbage’s original design: the machine worked perfectly.